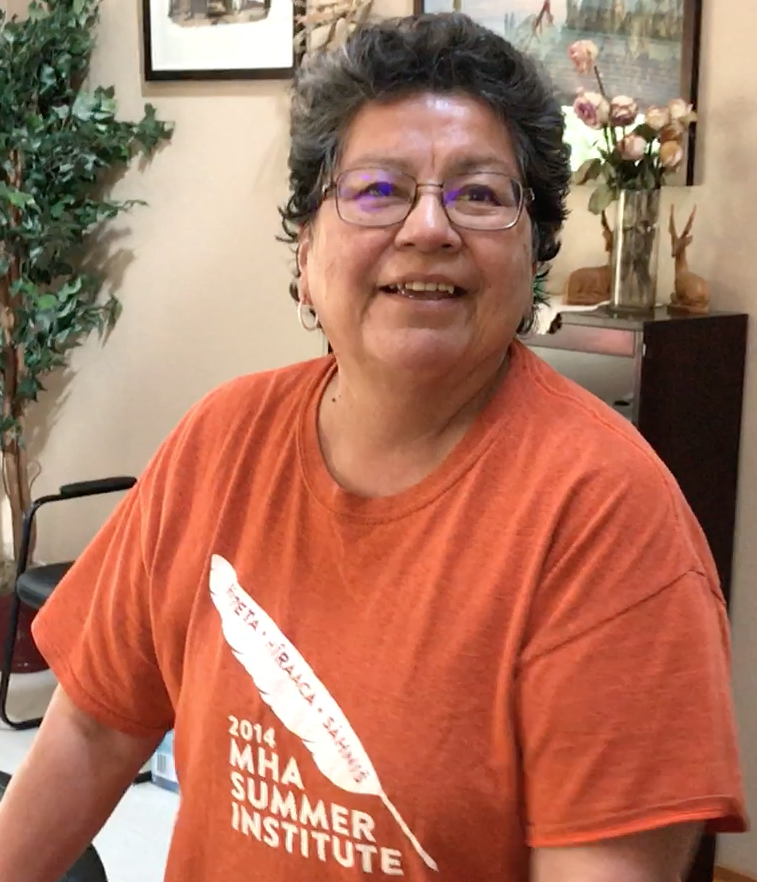

Bernadine Young Bird, of the Maxoadi Hidatsa clan, is a faculty member in the Native American Studies program at the Nueta Hidatsa Sahnish College, and coordinator of the MHA Summer Institute. She’s also founder & head gardener of Arugadi da Magoots: Returning to our Garden, a traditional Hidatsa garden inspired by Buffalo Bird Woman. The following remarks are lightly edited from interviews conducted a few weeks before the 2017 MHA Summer Institute.

The Challenge: Cultural Shifts

It’s not always easy to get people fired up about saving our languages and cultural practices. We’re in survival mode.

Our elders are leaving us so fast. We figure there’s about 100 fluent Hidatsa speakers. We [Hidatsa] used to be the most numerous [compared to Mandan and Arikara]. Now even we’re in crisis.

My generation, those in their ’50s and ’60s, are probably the last ones who had Hidatsa be their first language. We’re also the last ones who went to Boarding Schools. where we were punished for speaking the language. So people my age, even though we knew the language, we spoke more English.

We used to be afraid to speak in public. Not so much fear as maybe shyness, or stigma. I remember as a child speaking Hidatsa at the grocery store; but if other people came around, we would revert to English.

By the time my children were born, TV was a big thing. They were constantly exposed to English. So they picked it up real fast. My husband was fluent in Hidatsa, and we both spoke. But it didn’t filter down to our children.

Today’s generation, most don’t have a speaker in their home. They embrace other cultures: not only mainstream American culture, but Hispanic culture, Black culture, Asian culture, other cultures within our country.

So they’re multicultural, like most Americans. That’s fine. But what we’re concerned about is that they maintain their tribal identity. That hey are Nueta Hidatsa and Sahnish people first, as well as American citizens.

The Opportunity: We’re Still Here

I feel like our identity is still here. Many young people want to know about and participate in tribal activities. Most have been exposed to the language in our schools, and are learning some basic vocabulary and phrases. They know how to greet each other.

So they know some of the basics of the language, and they use them. They’re small things, but they’re big things. It’s good to hear them talking. Of course, we’re not building fluency. But they have knowledge.

Waking Up: the Oil Boom

Many immigrants moved here with the oil boom. And many people from here noticed how the newcomers would have have no qualms speaking Spanish or their other native languages in public.

That got some people thinking, and talking: “Gosh, remember how we used to be doing that? Remember how we would hear our language? Now we hear more Spanish than our own language!”

So it was kind of of an awakening. It planted a seed in people’s brains to bring our language back. We were already working on revitalizing our languages. But that made it even more evident how dramatic the loss had been.

The other thing of course is that we had more resources because of the oil. That enabled us be able to get help, like The Language Conservancy, who have the technological skills and expertise as linguists and language working with other tribes. So I think for us, the sense of urgency, coupled with the additional resources, got things going.

First Encounters: The Language Conservancy

Four years ago, I first went to the Language Conservancy’s Lakota Summer Institute in Standing Rock. That was an eye opener.

They talked about grammar, tenses, plurals, all of those things. I had never thought about teaching the language like that before. But that’s the way we learned English. It made sense to me. That’s a good technique.

This year, people are really excited about the apps developed by The Language Conservancy. That’s what our new learners need.

When you just look at a word, whether in the English alphabet or our own alphabet, there’s still a need to hear it to make sure to say it correctly. It’s one of the most beneficial things we’ve got. Not only in schools, but for adult learners of any age.

I’m not a techie person, but I’ve been really excited about them too! Until recently, I had a little flip phone. I didn’t have a phone you could download apps on. All I wanted to do was to connect with people. But my son insisted — “You better upgrade, mother!”

That really opened my mind. I’m of an older generation, but even I know the value of technology to teach language! I’m on board.

The most important thing, though, is that we want people to speak, not be afraid to speak. I always say: even if you make a little mistake, don’t worry about it, because it’ll come. You’ve got to keep practicing.

Coming soon: Part 2 of our talk with Bernadine, and her inspiring work on the Hidatsa Garden Project.